As global demographics shift, societies face an unprecedented test of financial resilience. The rise of older age groups places significant strain on existing pension arrangements, demanding innovative solutions and collective action.

By 2050, the number of people aged 60 and above will reach 2.1 billion worldwide, doubling the current figure. In 2022 alone, there were 771 million individuals aged 65 or older; projections estimate 994 million by 2030 and a remarkable 1.6 billion by 2050. Even more dramatic, the 80+ population is set to triple to 426 million within three decades.

Regions age at different rates. Latin America and the Caribbean will see one in five citizens over 65 by mid-century. In Africa, the share of seniors will triple, while Asia and low- to middle-income nations will host two-thirds of the world’s elderly. In Japan today, a striking 30% of inhabitants are over 60.

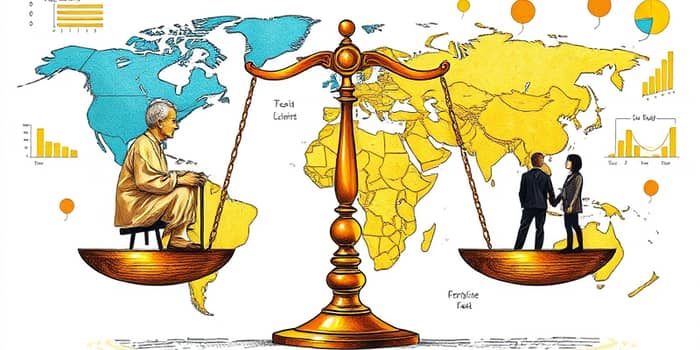

Several key forces underlie this demographic revolution. First, improved living conditions and healthcare have pushed life expectancy upward globally. Second, declining fertility rates mean fewer children entering the population mix. Together, these dynamics yield a rapidly growing proportion of retirees compared to workers, altering the balance of societal support.

As the dependency ratio climbs steadily, economies feel the pinch. A smaller workforce must sustain rising health costs, pension benefits, and other public programs. Labor shortages drive up wages and hinder productivity, potentially dragging down growth.

Immigration offers partial relief. Countries like Canada and Australia rely on skilled newcomers to bolster their labor forces. Yet integration challenges and fluctuating migration policies limit the long-term impact of this approach.

With more retirees drawing on benefits and fewer workers contributing, unsustainable pension commitments loom large. Governments face tough choices: reduce benefits, raise retirement ages, or divert resources from other public services.

Across major markets, global pension fund assets total approximately US$58.5 trillion, but even these vast sums may prove inadequate without reforms. Key policy responses include:

Developed countries like Japan and much of Western Europe face the most acute pension stress due to their already aged populations. Latin America, the Caribbean, and parts of Asia confront rapid aging without the spare fiscal headroom of wealthy nations. Meanwhile, Africa’s absolute numbers remain lower but its dependency ratios are rising fastest, challenging futures of economic development.

Policy adaptations vary. Sweden’s pension funds, among the highest ranked for sustainability practices among pension funds, experiment with blue bonds and fund mergers. In contrast, some low-income countries are still establishing basic contributory systems, relying heavily on family support networks.

Addressing pension sustainability requires collaboration among governments, employers, and individuals. By acting now, we can secure dignity for seniors and stability for future generations.

Technological innovation—automation, AI, and remote work—can mitigate workforce shortages. Meanwhile, intergenerational programs, community support networks, and age-friendly infrastructure strengthen social cohesion and reduce isolation.

The aging of global populations is unprecedented and enduring. Pension systems designed in eras of plentiful young workers must adapt swiftly. By combining policy reform, financial innovation, and societal engagement, we can transform the challenge into an opportunity—ensuring that every generation enjoys security, dignity, and shared prosperity.

References